This past week, I’ve been struggling with a nasty cold. Films give me comfort, and my brother recommended I watch Heretic, a horror film that had come out at the end of last year. I’m grateful for his recommendation; this is a really engrossing horror movie. There’s a lot about this film that’s really strong. Some aspects of it, though, I feel somewhat conflicted about, and I will talk through my feelings here.

The pacing of Heretic (written and directed by Scott Beck & Bryan Wood) is incredible. The writer-director duo possess a confidence in how they reveal their characters and the situations the characters are pulled into. The opening scenes depict Sister Paxton (Chloe East) and Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher), missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, making their way across town as they visit someone on their list of contacts of people who have reached out to the Church for more information. Through the conversations between the two missionaries and their brief encounters with some normal and some obnoxious townsfolk, the film reveals the lead characters’ contrasting personalities, dispositions, and outlooks. Paxton is a bit sunnier and more optimistic, while Barnes is more worldly and realistic.

The fact that more about these characters comes to light overtime, causing some aspects of the initial impressions of them to become more concrete while other elements become subverted or flipped, is a testament to the excellent performances by East and Thatcher, as well as the great writing. The gradual revelations, the developing dimensions, all feel believable. There’s so much more to the lead characters than at first glance, and we as audience members are invested in what happens to them. This is vital for so many stories but especially for a horror story that seeks to do more than just give cheap thrills.

This film definitely has more on its mind.

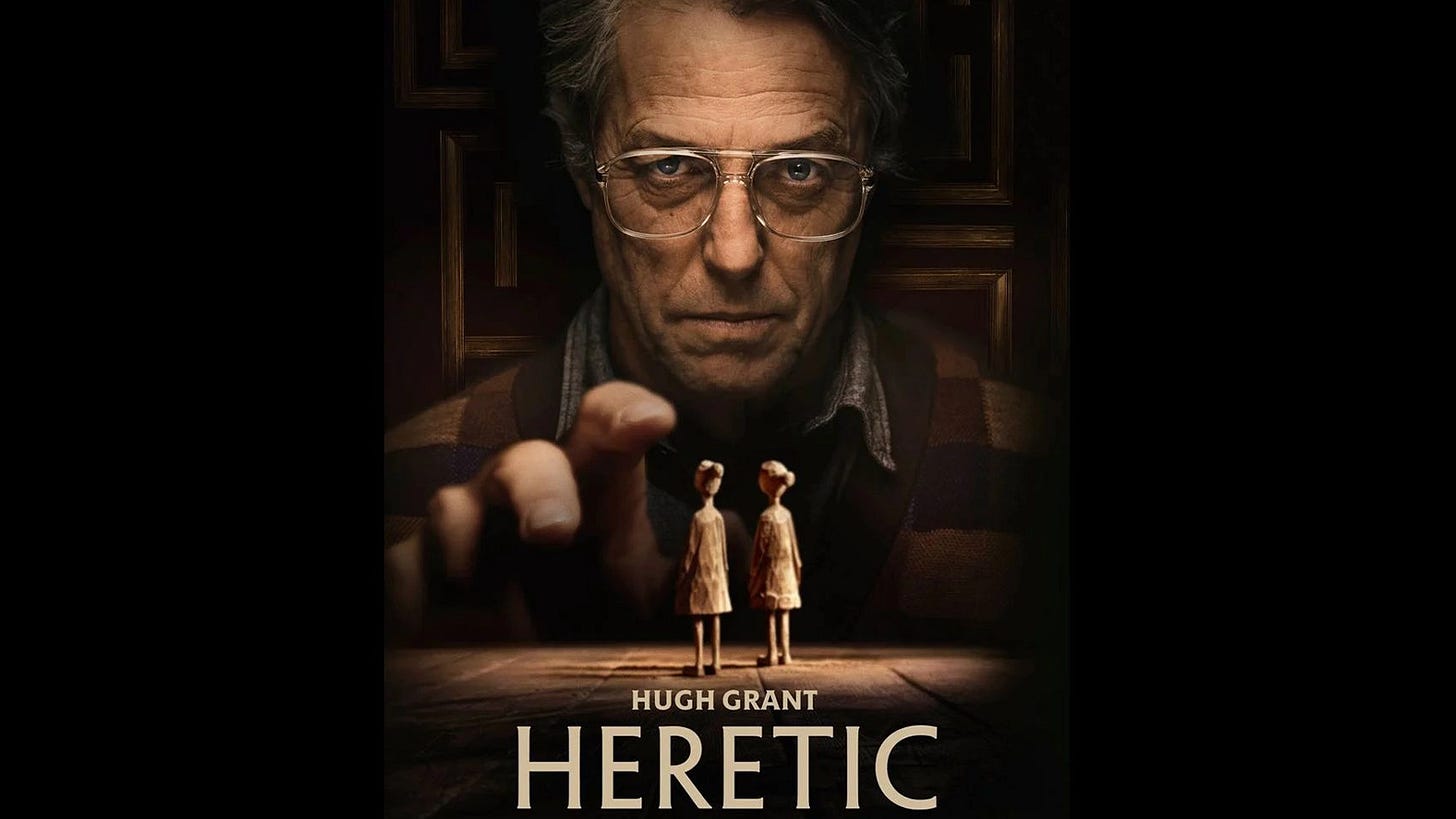

On an essential level, Barnes and Paxton are acting out of goodness and their best intentions. The same can’t be said about Mr. Reed (Hugh Grant), the person they end up visiting. The first red flag is that Barnes and Paxton insist that they cannot come inside Reed’s place unless his wife is there, and, though he claims she’s present, she doesn’t appear. Again, it speaks to the film’s pacing that this first red flag could just be a simple misunderstanding. Maybe Reed is just eager to talk with the missionaries.

In the first conversation with Reed, the elderly man comes off as very knowledgeable. He explains that he has studied religion for much of his life. His cynicism and skepticism come through at times, and Barnes and Paxton respond in the best ways they can. It is a lively, passionate conversation, and Reed is quite charming, while any moments of friction can be written off as awkwardness. Soon, however, Barnes and Paxton notice things that make them realize that they are in danger. What follows is a descent into the depths of the house, as Reed slowly reveals his true intentions. His actions straddle the line between eccentric and menacing until they tip completely into villainy. Things just get darker, creepier, more sinister. Room by room, the house morphs from a normal abode to a realm of nightmares. The escalation is absolutely riveting. While watching, I had no idea what to expect as the events transpired and one frightening revelation emerged after another.

The missionaries are in danger, and they must rely on each other and their inner resources to survive. Reed wishes to do harm. He also wants to prove a point. This puts him in the category of ideological villains, which I find to be some of the most memorable characters in the stories I read or watch. These villains don’t just want to do terrible and self-serving actions. They also want to prove that their ways of looking at the world are correct. They strive to make a point, to justify an ideology. Reed has a dark view of religion that he seeks to prove as correct through how he tests and toys with Paxton and Barnes, through how he seeks to ruin them.

This is the aspect of the film that I have mixed feelings about. While I appreciate the ideological battle between the missionaries and their opponent, a battle that springs out of the missionaries’ physical quest for survival, I found myself after the end credits wondering if this philosophical/theological layer was just surface level or if it ran deeper. Was it just a flavoring to make this horror film distinct? There’s nothing wrong with that at all; there are all sorts of ways to make a genre film more particular. Or, was it woven more deeply into the plot, the setting, the atmosphere? Was it not just seasoning but a foundational ingredient?

What helps clarify my feelings about Heretic is drawing a comparison to one of my favorite films, which I’ve discussed here earlier: Prisoners. Minor spoiler alert. The antagonistic force in Prisoners can also be deemed as an ideological villain. They, like Reed, are waging a theological battle through their monstrous actions. They have a horrifying point to make. Prisoners, from my perspective, is a meditation of faith, belief, and doubt because of the various journeys the multiple characters take. Also, Prisoners asks the audience to reflect on their own relationships with doubt and belief.

It’s hard to talk about specific elements of Heretic without spoiling it. I want to save as much of it as I can from spoilers because I do think it’s a worthwhile horror film. The performances are great. The pacing is amazing. The escalation is gripping. I do recommend this film to anyone who is a fan of horror and anyone who appreciates when a film includes elements that touch on philosophy and theology.

Minor spoilers follow: I think the ending is somewhat ambiguous, and that it does ask audiences to reflect on their own beliefs and worldviews. In terms of the ideological battle at the center of the film, some characters lose more clearly than other characters do. There is no clear winner. This ambiguity is welcome because matters of faith, by definition, don’t have clear cut answers. Yet, even through ambiguity, a film can say something deep or interesting about faith and religion. This film does make belief, religion, and theology aspects of its plot, but I don’t think the movie ultimately makes a strong point about them. The missionaries don’t exactly go on spiritual journeys or significant changes in faith. While I’ve come to conclude that the theological aspects aren’t surface level only, they don’t go as deeply as I wanted them too.

And this, ultimately, is just a personal preference. I understand that it feels weird to want a film to match my particular expectations for it. It of course doesn’t have to do that.

The thing is, though, the film somewhat aroused these expectations. There’s a moment in which Reed states that disbelief is terrifying because there’s a possibility that nothing matters, that our lives have no meaning. This idea has truth to it. Whatever we believe, whether we believe in God, love, justice, goodness, and/or hope, our beliefs possess an undercurrent of fear because they open the door to the possibility that we might be wrong. They aren’t knowledge, just beliefs. What we know, we can be sure of. But what we believe can be wrong. There may be no God, no love, no justice, no goodness, no hope. Faith, in a way, is a response to existential terror. Faith and horror are linked.

This film could have touched on that a bit more, through some of the plot, or through some of the exchanges between the characters, or through more drastic character arcs. Still, though, I appreciate that this film did get me to reflect on the relationship between faith and fear. Its inclusion of lofty ideas thus produces a significant impact, even if those lofty ideas aren’t navigated as thoroughly as they could have been. Overall, I appreciate its attempt.

This is a very good film. Scott Beck & Bryan Wood have also worked on the screenplay for A Quiet Place and have written and directed Haunt; both of these are very good horror films that I appreciate immensely. I’m excited for their future projects.

Great review!

I appreciate your perspective on this! I liked the intellectual aspect as well. Grant's character was intriguing because of this. He seems reasonable at first and even his earlier taunts and menaces seem to have reason to them, but that devolves as the story goes on as he seems to lose some control over what his narrative of the charade is supposed to be. And maybe that speaks to his evil winning out over his intellectualism.